Two new treatment methods under investigation at Drexel University aim to help people reduce binge-eating behavior.

A smartphone app in development will track users’ individual patterns of eating and binge eating behavior and alert them at times when they are at risk for binge behaviors, among a comprehensive suite of other features.

Another treatment is a new, evidence-based approach to small-group behavioral therapy that will equip patients with psychological tools that may help them adhere to, and benefit from, standard treatments for binge eating disorder.

Binge eating disorder, characterized by periods of eating objectively large amounts of food, is “associated with a great deal of clinical distress,” said Dr. Evan Forman, an associate professor of psychology in Drexel’s College of Arts and Sciences, co-director, with Dr. Meghan Butryn, of the Laboratory for Innovations in Health-Related Behavior Change, where both studies are being conducted.

Binge eating disorder, only recently identified as an official diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, was found to be about twice as common as bulimia nervosa in a large international survey published earlier this week.

People who engage in binge eating behavior may feel ashamed, out of control and isolated because they may not know others with the disorder, or even know they have a clinically recognized disorder.

The most scientifically supported treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), leads to remission for only between 50-60 percent of individuals who complete a full course of treatment.

“It could be improved,” Forman said. “These two studies are an attempt to improve treatments for binge eating.”

A Mobile App for Binge Eating Disorder

Among binge eaters, “there is a cycle of sorts – mounting pressure toward a binge episode, with certain triggers that make it more likely that a binge episode will occur,” Forman said. With cognitive behavioral therapy, a clinician helps patients recognize their personal triggers and learn to interrupt them.

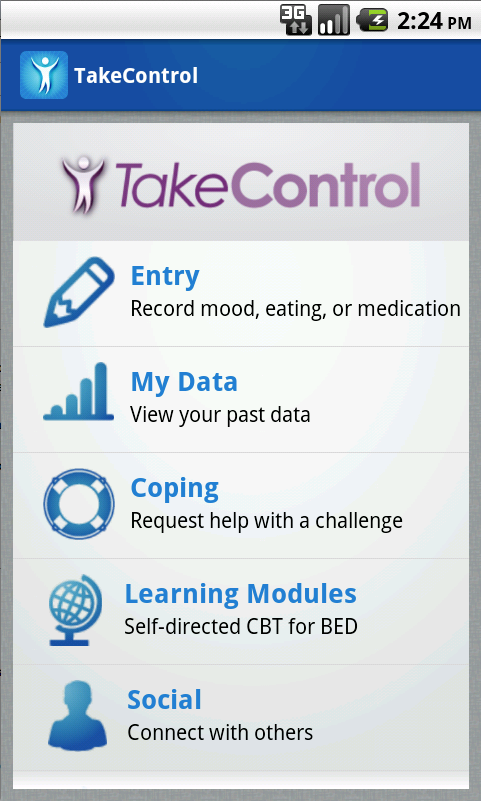

Forman’s lab is developing the “TakeControl” mobile phone app to provide a similar help right in the patient’s pocket – and in real time, at the moment the trigger occurs.

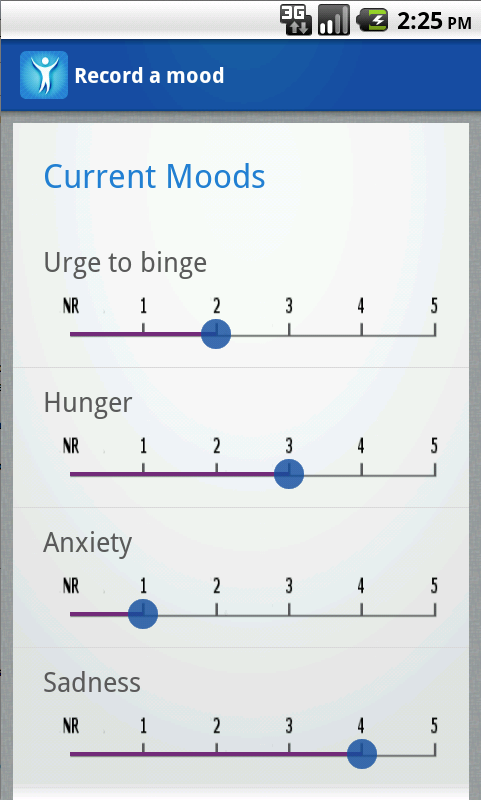

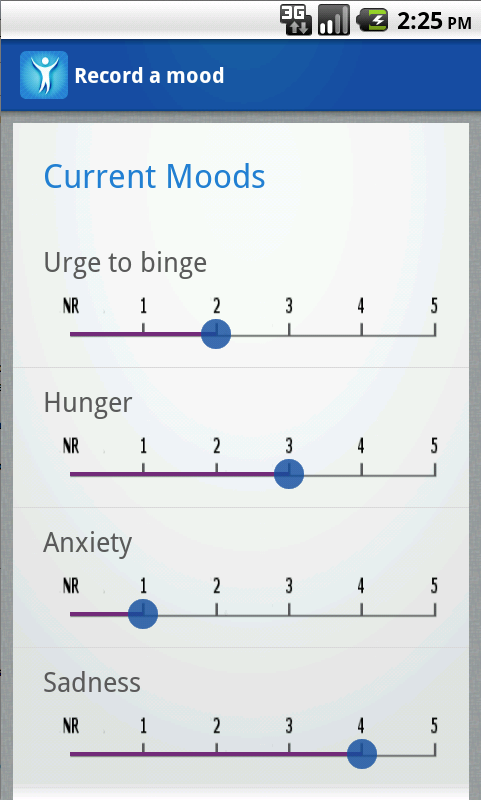

In the app, users can record their binge-eating activity and urges, multiple mood states and whether or not they’ve eaten regular meals and taken their prescription medications. As the app learns about an individual’s patterns of binge-eating behavior and their individual triggers, it can prompt the person with a warning alert when their personal risk is high.

“It could be an emotion like rejection, loneliness, sadness or anxiety, or something external such as passing a certain convenience store, or a time of day or night,” said Forman, who is the principal investigator of the project.

When warned that they are at risk for a binge, or at any time of their own choosing, users can follow the app’s customized interventions to help them in the moment when they need it.

Users of the “TakeControl” app can choose how much and how little of their personal data to enter to help the app help them. The app also includes learning modules, optional personal goal-setting modules and optional social networking features to connect with others who share this often-isolating disorder.

“Using the data visualization modules, people can chart their behavior patterns over time,” said Stephanie Goldstein, a graduate student in Forman’s lab working on the project. “This shows people the progress they’ve made and reinforces it. Someone could also learn from the charts, for example, how their binges relate to their anxiety.”

Forman’s research team is developing the app on the Android platform in collaboration with the Applied Informatics Group in Drexel’s College of Computing and Informatics.

“Most users have their smartphone with them upwards of 20 hours a day, so a mobile app can be a very effective way to monitor behaviors that a physician wouldn’t automatically know about,” said Gaurav Naik, a co-investigator on the project from the AIG. “By combining AIG’s knowledge of engineering systems that can learn from data, and the clinical knowledge of our partners in psychology, we can develop an app that we hope can generate successful outcomes.”

The project was one of two winners selected in an internal university-wide competition under the auspices of a Shire Pharmaceuticals-Drexel University Innovation Partnership. In December 2013, each project will be considered by Shire for further expansion and commercialization. If funded, the group expects to also develop a version for iOS.

Future plans for the app include connections with other technologies for automatic personal data tracking, such as smart pill bottles, web-connected scales and activity bands, as well as existing popular diet and fitness-tracking apps.

Users of the app will also have the option to share their data with their therapist or other clinician, either automatically through a clinician’s portal, or by bringing their exported data to a therapy session.

Therapy to Help the Therapy Work Better

“Standard treatment for binge eating disorder is largely behavioral – in that it tells people what to do,” said Dr. Adrienne Juarascio, a postdoctoral fellow in Forman’s lab who is the principal investigator of the in-person treatment study. “In CBT we ask people to adhere to uncomfortable treatment recommendations, such as eating every three to four hours even when they are concerned about weight gain. Or they might be asked to engage in alternative activities while they are having the urge to binge.

“It can be very difficult to complete these treatment recommendations, no matter how motivated people are.”

Juarascio is now coordinating an experimental treatment program for binge eating disorder that teaches patients psychological strategies to deal with the discomfort associated with traditional treatments.

The 10-session group therapy program integrates the gold-standard cognitive behavioral therapy with another method, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and other third generation acceptance-based behavioral treatments, to help patients learn to tolerate and accept stressful experiences and distressing thoughts, without engaging in disordered behaviors.

“Different people find it uncomfortable for different reasons,” Forman said. “For example, if someone had binged the night before and thought, ‘There’s no way I’m eating breakfast after that,’ the ACT skills are designed to help the person recognize this feeling of being repulsed by food, and proceed to eat breakfast anyway because consistently eating regular meals is healthier in the long run.”

Juarascio previously piloted the approach, combining treatment-as-usual with ACT in the treatment of eating disorders more broadly, as part of her doctoral research at Drexel. In the July 2013 issue of the journal Behavior Modification, she, Forman and other colleagues reported that patients receiving the combined therapy had better outcomes at a six-month follow-up than did those receiving standard treatments.

– See more at: http://drexel.edu/now/archive/2013/September/Binge-Eating-Smartphone-App-Therapy-Studies/