Originally posted on DrexelNow.

Scientists have discovered and described a new supermassive dinosaur species with the most complete skeleton ever found of its type. At 85 feet (26 m) long and weighing about 65 tons (59,300 kg) in life, Dreadnoughtus schrani is the largest land animal for which a body mass can be accurately calculated. Its skeleton is exceptionally complete, with over 70 percent of the bones, excluding the head, represented. Because all previously discovered supermassive dinosaurs are known only from relatively fragmentary remains, Dreadnoughtus offers an unprecedented window into the anatomy and biomechanics of the largest animals to ever walk the Earth.

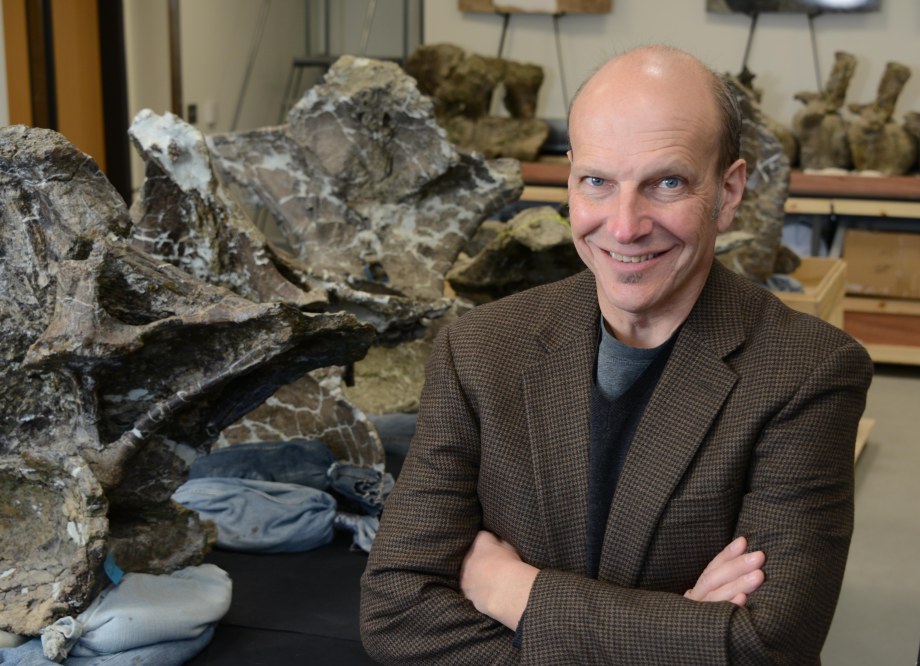

“Dreadnoughtus schrani was astoundingly huge,” said Kenneth Lacovara, PhD, an associate professor in Drexel University’s College of Arts and Sciences, who discovered the Dreadnoughtus fossil skeleton in southern Patagonia in Argentina and led the excavation and analysis. “It weighed as much as a dozen African elephants or more than seven T. rex. Shockingly, skeletal evidence shows that when this 65-ton specimen died, it was not yet full grown. It is by far the best example we have of any of the most giant creatures to ever walk the planet.”

Lacovara and colleagues published the detailed description of their discovery, defining the genus and species Dreadnoughtus schrani, in the journal Scientific Reports from the Nature Publishing Group today. The new dinosaur belongs to a group of large plant eaters known as titanosaurs. The fossil was unearthed over four field seasons from 2005 through 2009 by Lacovara and a team including Lucio M. Ibiricu, PhD, of the Centro Nacional Patagonico in Chubut, Argentina, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Matthew Lamanna, PhD, and Jason Poole of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, as well as many current and former Drexel students and other collaborators.

Over 100 elements of the Dreadnoughtus skeleton are represented from the type specimen, including most of the vertebrae from the 30-foot-long tail, a neck vertebra with a diameter of over a yard, scapula, numerous ribs, toes, a claw, a small section of jaw and a single tooth, and, most notably for calculating the animal’s mass, nearly all the bones from both forelimbs and hindlimbs including a femur over 6 feet tall and a humerus. A smaller individual with a less-complete skeleton was also unearthed at the site.

The ‘gold standard’ for calculating the mass of quadrupeds (four-legged animals) is based on measurements taken from the femur (thigh bone) and humerus (upper arm bone). Because the Dreadnoughtus type specimen includes both these bones, its weight can be estimated with confidence. Prior to the description of the 65-ton Dreadnoughtus schrani specimen, another Patagonian giant, Elaltitan, held the title of dinosaur with the greatest calculable weight at 47 tons, based on a recent study.

Overall, the Dreadnoughtus schrani type specimen’s bones represent approximately 45.3 percent of the dinosaur’s total skeleton, or up to 70.4 percent of the types of bones in its body, excluding the skull bones. This is far more complete than all previously discovered giant titanosaurian dinosaurs.

“Titanosaurs are a remarkable group of dinosaurs, with species ranging from the weight of a cow to the weight of a sperm whale or more. But the biggest titanosaurs have remained a mystery, because, in almost all cases, their fossils are very incomplete,” said Matthew Lamanna.

For example, Argentinosaurus was of a comparable and perhaps greater mass than Dreadnoughtus, but is known from only a half dozen vertebrae in its mid-back, a shinbone and a few other fragmentary pieces; because the specimen lacks upper limb bones, there is no reliable method to calculate a definitive mass of Argentinosaurus. Futalognkosaurus was the most complete extremely massive titanosaur known prior to Dreadnoughtus, but that specimen lacks most limb bones, a tail and any part of its skull.

To better visualize the skeletal structure of Dreadnoughtus, Lacovara’s team digitally scanned all of the bones from both dinosaur specimens. They have made a “virtual mount” of the skeleton that is now publicly available for download from the paper’s open-access online supplement as a three-dimensional digital reconstruction.

“This has the advantage that it doesn’t take physical space,” Lacovara said. “These images can be ported around the world to other scientists and museums. The fidelity is perfect. It doesn’t decay over time like bones do in a collection.”

“Digital modeling is the wave of the future. It’s only going to become more common in paleontology, especially for studies of giant dinosaurs such as Dreadnoughtus, where a single bone can weigh hundreds of pounds,” said Lamanna.

The 3D laser scans of Dreadnoughtus show the deep, exquisitely preserved muscle attachment scars that can provide a wealth of information about the function and force of muscles that the animal had and where they attached to the skeleton – information that is lacking in many sauropods. Efforts to understand this dinosaur’s body structure, growth rate, and biomechanics are ongoing areas of research within Lacovara’s lab.

A Dinosaur that Feared Nothing

Illustration: Jennifer Hall

“With a body the size of a house, the weight of a herd of elephants, and a weaponized tail, Dreadnoughtus would have feared nothing,” Lacovara said. “That evokes to me a class of turn-of-the-last century battleships called the dreadnoughts, which were huge, thickly clad and virtually impervious.”

As a result, Lacovara chose the name “Dreadnoughtus,” meaning “fears nothing.” “I think it’s time the herbivores get their due for being the toughest creatures in an environment,” he said. The species name, “schrani,” was chosen in honor of American entrepreneur Adam Schran, who provided support for the research.

To grow as large as Dreadnoughtus, a dinosaur would have to eat massive quantities of plants. “Imagine a life-long obsession with eating,” Lacovara said, describing the potential lifestyle of Dreadnoughtus, which lived approximately 77 million years ago in a temperate forest at the southern tip of South America.

“Every day is about taking in enough calories to nourish this house-sized body. I imagine their day consists largely of standing in one place,” Lacovara said. “You have this 37-foot-long neck balanced by a 30-foot-long tail in the back. Without moving your legs, you have access to a giant feeding envelope of trees and fern leaves. You spend an hour or so clearing out this patch that has thousands of calories in it, and then you take three steps over to the right and spend the next hour clearing out that patch.”

An adult Dreadnoughtus was likely too large to fear any predators, but it would have still been a target for scavengers after dying of natural causes or environmental disasters. Lacovara’s team discovered a few teeth from theropods – smaller predatory and scavenging dinosaurs– among the Dreadnoughtus fossils. However, the completeness and articulated nature of the two skeletons are evidence that these individuals were buried in sediments rapidly before their bodies fully decomposed. Based on the sedimentary deposits at the site, Lacovara said “these two animals were buried quickly after a river flooded and broke through its natural levee, turning the ground into something like quicksand. The rapid and deep burial of the Dreadnoughtus schrani type specimen accounts for its extraordinary completeness. Its misfortune was our luck.”

Further Information and Resources

For a full suite of resources, including multimedia content available for use by the news media, please see the collection of links on the Dreadnoughtus Media Resource Page.

Link to paper (on and after Sept. 4, 2014): http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep06196

Primary collaborators on the study with Lacovara were Matthew C. Lamanna, PhD of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh and Lucio M. Ibiricu, PhD of the Centro Nacional Patagonico in Chubut, Argentina, who began working with Lacovara as an undergraduate volunteer during the Dreadnoughtus excavation and went on to earn his doctoral degree at Drexel University. Lamanna was first author on a recent paper describing the dinosaur Anzu wyliei, popularly known as the “chicken from Hell.”

Additional co-authors are: Jason C. Poole, Dinosaur Hall Coordinator at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University; Elena R. Schroeter, PhD, who recently earned her doctoral degree for her work on Dreadnoughtus in Lacovara’s lab at Drexel; Paul V. Ullmann, Kristyn K. Voegele and Zachary M. Boles, doctoral candidates in Lacovara’s lab at Drexel; Aja M. Carter, a 2014 Drexel Biology alumna who contributed to Dreadnoughtus preparation as an undergraduate; Emma K. Fowler, an undergraduate Drexel student; Victoria M. Egerton, PhD of the University of Manchester, who earned her doctoral degree in Lacovara’s lab; Alison E. Moyer, a 2008 Drexel alumna who was part of the Dreadnoughtus excavation in Argentina as an undergraduate and is now a doctoral candidate in paleontology at North Carolina State University; Christopher L. Coughenour, PhD, who earned his doctoral degree in Lacovara’s lab at Drexel and is now at the University of Pittsburgh, Johnstown, PA. campus; Jason P. Schein of the New Jersey State Museum; Jerald D. Harris, PhD, of Dixie State College in St. George, Utah; Ruben D. Martínez, PhD of the Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco in Chubut, Argentina; and Fernando E. Novas, PhD, of the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales in Buenos Aires.

Lacovara, Lamanna and Poole were previously among the co-authors describing Paralititan stromeri, a large titanosaur which they excavated from the Egyptian Sahara.

Under Argentinian law, the Dreadnoughtus fossils are the property of the federal government in Argentina and are to be retained permanently in the province where they were discovered, Santa Cruz. The fossils were transported to Philadelphia and Pittsburgh in 2009 for scientific preparation and analysis under a research loan agreement. Fossil preparation and analysis occurred at Drexel University, the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University and Carnegie Museum of Natural History. All Dreadnoughtus fossils are currently at Drexel University and will be returned to their permanent repository at the Museo Padre Molina in Rio Gallegos, Argentina, in 2015.

Funding sources for the study of Dreadnoughtus include the National Science Foundation (EAR Award 0603805 and three Graduate Research Fellowships [DGE Award 1002809]), the Jurassic Foundation, R. Seidel, Drexel University, The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and supporting donor Adam Schran.

– See more at: http://drexel.edu/now/archive/2014/September/Dreadnoughtus-Dinosaur/