When you think of tropical biodiversity, you may picture flocks of colorful birds flitting through lush foliage—but what you are less likely to imagine is the plethora of parasites and pathogens pulsing through the bloodstreams of those birds. Among these microscopic organisms are Plasmodium parasites, best known for causing malaria in humans, birds and many other vertebrates.

A new study published this week in the journal PLOS ONE explores the scope of malaria parasite diversity in southeast African birds, and provides insight into how lifestyle characteristics of birds can influence their association with different parasite genera. The study considers haemosporidian (blood) parasites in the genus Plasmodium, as well as closely-related parasites in the genera Haemoproteus and Leucocytozoon. Understanding the patterns of how those parasites are transmitted across populations and different species of birds can help unlock a better understanding of disease movements in the environment.

Among hundreds of birds sampled during two months of field work in the southeastern African nation of Malawi, an astonishing proportion of the birds—79 percent—were infected with haemosporidian parasites. Even more surprising was the number of novel malaria parasite lineages scientists discovered in Malawian birds.

“A large proportion, 81 percent, of the parasites that we detected are new, previously undocumented lineages of Plasmodium, Haemeoproteus and Leucocytozoon,” said study co-author Jason Weckstein, PhD, an associate professor at Drexel University in the College of Arts and Sciences and the associate curator of ornithology at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

The study, led by Holly Lutz, a PhD candidate at Cornell University, was conducted under the auspices of the Emerging Pathogens Project at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, and included collaborators from the Field Museum, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the University of North Dakota. Lutz and Weckstein began collaborating when Lutz was an undergraduate student at the University of Chicago and worked with Weckstein on a National Science Foundation funded project.

“We typically think of malaria as a human disease, but in reality, the vast majority of haemosporidian parasites infect birds, reptiles and non-human mammals,” said Lutz. “Studying how other animals interact with and combat these parasites could provide us with important insights for the fight against human malaria.”

The effects of these parasites in wild animals range from mild to severe. In one of the most dramatic examples, avian Plasmodium parasites introduced by humans to naïve bird communities in Hawaii ultimately led to the extinction of at least 10 native bird species. Despite such devastation in Hawaiian birds, the effect of naturally occurring haemosporidian parasites in wild populations is poorly known.

By studying a large and diverse sample of birds, Lutz, Weckstein and their colleagues were able to draw several associations between birds’ lifestyle habits and their patterns of parasitic infection: “We found that bird species aggregating in single-species flocks experienced a lower probability of infection by Plasmodium parasites and a higher probability of infection by Haemoproteus parasites, relative to birds that are solitary or living in mixed-species flocks,” Weckstein said.

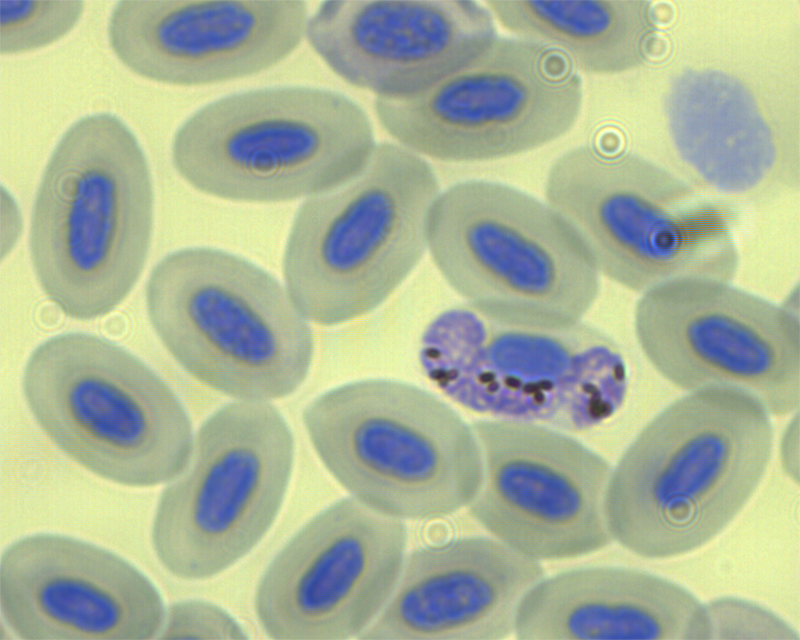

Haemoproteus parasites infect one of the red blood cells shown in this sample taken from a bird in Malawi. Credit: Jacob Mertes, University of North Dakota

The diversity of parasites found here indicate that this region of southeast Africa is a prime area to study the mechanisms of host-parasite interactions—and, Weckstein said, knowing more about the diversity of haemosporidian parasites infecting birds here helps complete the picture across Africa. Scientists now have data from across the continent, including Malawi, Mozambique, Congo, Uganda and Kenya. “This will increase our sample sizes and give us a chance to look more broadly at how host specific some of these parasites are (how many host species they infect) and how geographically specific they are (whether particular parasites are only found in some regions and not others).”

Weckstein hopes future research will yield more information about the vector species that transmit the parasites between avian hosts. Based on the high prevalence and diversity of haemosporidian parasites found in this region, the fly and mosquito species which transmit these parasites are believed to have diverse lifestyle characteristics as well. The patterns of infection that vary between birds with different lifestyle habits likely reflect differences in the biology of vector insects. Understanding these vector species is critical to making sense of the complex interactive systems involving diverse sets of hosts, parasites and vectors in this environment.

– See more at: http://drexel.edu/now/archive/2015/April/African-Birds-Malaria-Diversity/#sthash.7up1SZ1o.dpuf

Originally posted on

Originally posted on